Addressing Resistance to Increase Participation in Group Therapy

Ideally, the therapy group would run smoothly, all the participants would walk away feeling fulfilled, and the therapist could rest easy at night knowing they did their best to facilitate a helpful group. In reality, though, resistance in group therapy is a common and expected facet of the group experience. Instead of being bogged down by it, great therapists learn how to use resistance and ambivalence as agents for change.

Therapists who do not will quickly find themselves shying away from therapy groups or facilitating groups with dwindling numbers. To help clients thrive, therapists must learn effective strategies to increase participation in group therapy by identifying, understanding, and transforming resistive behaviors. The result will be a more cohesive and engaged therapy group that serves as a supportive environment for all participants.

Free Patient Handout: Getting the Most Out of Group Therapy

Download this informative handout that will help your clients get the most out of their participation in group therapy.

Understanding Resistive Behavior in Group Addiction Therapy

Resistive behavior in group addiction therapy is any action or lack of action that hinders the therapeutic process for the client, other group members, or the therapist. Healthy therapy groups rely on an equilibrium to function well, and resistance can upset the balance in obvious ways. Resistance can become contagious from one member to another and jeopardize the role of the therapist as a person who can successfully facilitate the sessions.

Just like conflict in group therapy, resistance is not necessarily a bad thing. Often, there is a legitimate concern pushing the client towards these resistance behaviors in group therapy, whether they realize it or not. They are experiencing some stress, struggle, or discomfort and use resistance to communicate it. As the therapist, there are two options:

- Label the client as oppositional, defiant, inappropriate, or attention-seeking and swiftly remove them from group

- Work to build a deeper understanding of the client’s experience and build a case conceptualize that holds an explanation for their resistance

As with everything therapists do, the facilitator has to look beyond the obvious to understand the function of these actions. With understanding, the therapist can work within the context of the group therapy to identify and shift this resistance towards something more desirable and appropriate for the client. Just because a client is resistant does not mean they are a bad client.

Types of Resistance in Group Therapy

Whether verbal or nonverbal, intentional or unplanned, resistance can present in a myriad of ways. Some acts of resistance will be covert and challenging to identify, while others will be bold and obvious. These types of resistance in group therapy may seem very different, but they could work to communicate the same distress.

Examples of common shows of resistance in group therapy include:

- Presenting to session intoxicated, late, or not coming at all

- Refusing to participate

- Being distracted during session - looking at phone, bringing in crossword puzzles, wearing headphones

- Being a distraction by moving their seat, fidgeting, or speaking off topic

- Falling asleep during session

- Failing to maintain payment or insurance information needed to continue sessions

- Questioning therapist’s abilities, ethics, or empathy

- Inappropriately calling out the actions or opinions of other group members

These acts of resistance work to shift the focus and attention within the group, either toward or away from the resistant client. The group as a whole suffers when resistance continues for extended periods because it consumes a lot of time and energy.

Depending on the response from the therapist, the shows of resistance could shrink or multiply quickly. Before long, one group member could be engaging in all of the examples of resistance above and finding very creative ways to disrupt the session.

How to Deal with Resistance in Group Therapy

Like other conflict-management concerns in group therapy, the facilitators could implement any number of solutions to improve participation in therapy groups. Depending on the group duration, how well clients know and respect each other, and the function of the group, the therapist could be very active or very passive.

For example, if there is a new group dealing with assertive communication with clients who are unfamiliar with each other, the therapist could tightly manage the appearance of resistance. They could point out the behavior as unwanted and offer clear and concise consequences should these actions continue.

Alternatively, in a well-established group, the therapist could take a different role and encourage the group to police itself. Having the other group members take pride in and responsibility for the group process can help create a strong, cohesive team.

Resolving resistance in group therapy is an opportunity for the therapist to apply their science in the most artful way possible. The therapist must consider various client attributes like:

- Age, gender, sexual orientation

- Communication style

- Response to assertive communication and boundaries

- Possible explanations for their resistance

- History of resistance

- Connections to therapist and group members

Based on these factors, the therapist chooses a path forward that balances empathy with firmness and rigidity with flexibility. Remember, working through resistance in group therapy is a must. Just because it is uncomfortable does not mean it’s bad.

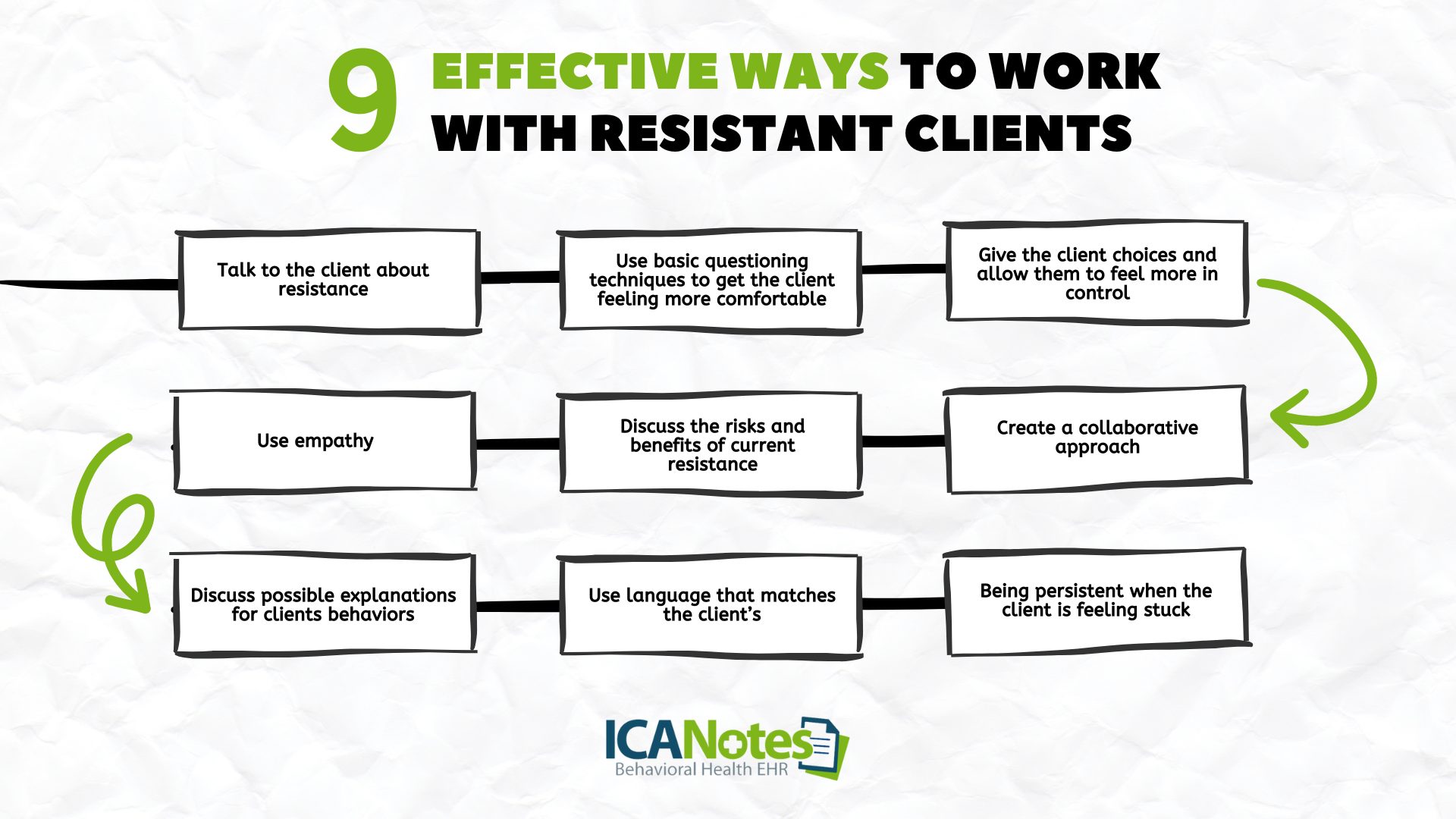

9 Effective Ways to Work with Resistant Clients

Some of the best ways to address resistance in clients and improve participation in therapy groups is to:

- Talk to the client about resistance

- Use basic questioning techniques to get the client feeling more comfortable

- Give the client choices and allow them to feel more in control

- Create a collaborative approach

- Discuss the risks and benefits of current resistance

- Use empathy

- Discuss possible explanations for clients behaviors

- Use language that matches the client’s

- Being persistent when the client is feeling stuck

Theoretical Views of Resistance

The way a therapist views resistance has a lot to do with their theoretical orientation, education, and experience. Identifying and understanding the impact of orientation and training will help guide the process.

- Traditional or psychoanalytic therapists may see resistance as a defense mechanism as the clients work to block thoughts from becoming conscious.

- Behaviorists may view resistance stemming from a lack of client skill or the client believing therapy produces unwanted outcomes.

- Person/ client-centered therapists can view resistance as an avoidance of unpleasant thoughts or feelings.

- Family systems theorists see resistance as a way to protect family members and avoid change when change is associated with betrayal and disloyalty.

Working Through Therapist Resistance in Group Therapy

Clients are not the only ones who become resistant in group therapy. There are occasions when therapists themselves become resistant to the process or a group member and create problems for current and future sessions.

Therapists may become resistant due to:

- Overall burnout and compassion fatigue

- Being triggered or experiencing countertransference

- Feeling inadequate to move the group forward

- Lacking empathy for the group member or their situation

No matter the influence, therapist resistance will break down the group process and spur additional resistance and conflict from members. To address this, the therapist must take an honest and open look at their experience in the group and how they are contributing to resistance. If the therapist is too quick to scapegoat group members, more and more resistance will begin because the true source is not being addressed.

Strategies to Increase Participation in Group Therapy

If resistance is the problem, increased participation in group therapy is the goal. Therapists should work to build the keen ability to differentiate between forced and authentic improved participation in the therapy group. Here, quality of participation is more important than quantity. A group member may speak for a long time without actually disclosing much.

To aid the process, therapists should spend some time speaking about the benefits of appropriate group participation. Let clients know what ideal participation looks and sounds like and how nonverbal communication plays a role. In addition, pointing out the desirable communication levels of other group members will help shape and reinforce wanted participation levels.

Final Thoughts

Resistance behavior in group therapy can quickly derail the treatment process and negatively affect all members of the group. Resistance is not the enemy, though. Poor reactions to resistance are the real problem.

Therapists have a difficult task in orchestrating and responding to the actions of everyone in the room, including themselves, but by understanding and responding to resistance, the group will function in a better balance. Effectively addressing resistance and ambivalence will ultimately improve participation in therapy groups and improve outcomes.

Using ICANotes may not help you reduce resistance in therapy groups, but it will give you a powerful tool to quickly and accurately document the ebbs and flows of resistance in all of your therapy groups. This way, you can be better able to identify trends and patterns of resistance to resolve the next occurrence before it even starts. ICANotes features a group therapy notes module that significantly reduces the time spent documenting your group session notes.

Book a demo and find out how to streamline your documentation process:

About the Author

Eric Patterson, MSCP, NCC, LPC

Eric Patterson, MSCP, NCC, LPC, is a professional counselor who has been working for over a decade to help children, adolescents, and adults in western Pennsylvania reach their goals and improve their well-being.

Along the way, Eric worked as a collaborating investigator for the field trials of the DSM-5 and completed an agreement to provide mental health treatment to underserved communities with the National Health Service Corp.

Sources

Fenchel, G.H. (1985). Resistance in Group Psychotherapy, GROUP.

Shallcross, Lynne. (2010). Managing Resistant Clients, Counseling Today.

Resenthal, Leslie. (1996). Phenomena of Resistance in Modern Group Analysis, American Journal of Psychotherapy.

Watson, J.C. (2006). Addressing Client Resistance: Recognizing and Processing In-Session Occurrences, VISTAS.