Orthorexia Nervosa: Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Treatment Strategies

Orthorexia nervosa symptoms, such as an obsessive focus on eating “clean” or “healthy” foods, can significantly impact mental and physical well-being. This eating behavior, often fueled by rigid dietary rules, can evolve from a genuine interest in wellness into a disordered eating pattern. Understanding orthorexia nervosa treatment is crucial, as a multidisciplinary approach involving therapists, dietitians, and medical professionals can help individuals recover and regain balance in their lives. While orthorexia nervosa is not yet an official diagnosis, it remains a serious concern requiring attention from clinicians and researchers alike.

When seeking various tips and tricks for wellness, a few common themes pop up: connect with others, move your body, get good sleep, drink enough water and eat well. These (among others) are some of “the basics” we often consider when attempting to maintain wellness or improve our physical or mental health. For many, this introspection can turn into a helpful approach to maintaining overall well being. For some, their concern for wellness can slowly go from supportive to detrimental. When it comes to nutrition in particular, excessive preoccupation with eating “healthy” for the sake of wellness can turn into disordered eating or an eating disorder.

Preoccupation with “Healthy” Eating

Orthorexia nervosa, first introduced by Dr. Steven Bratman in the late 1990s, is a term used to describe an excessive preoccupation with “healthy” or “clean” eating.[1]

Orthorexia shows up as rigid and inflexible beliefs and behaviors around food - particularly regarding the need for food to be “clean,” “healthy” or “pure.” It can be overwhelming, consuming the impacted person’s mind and time. Like most health concerns, intensity of symptoms and their impact on the individual can vary. Orthorexia has the potential to worsen mental and physical health, strain relationships, and make maintaining school, work, or hobbies difficult or impossible.

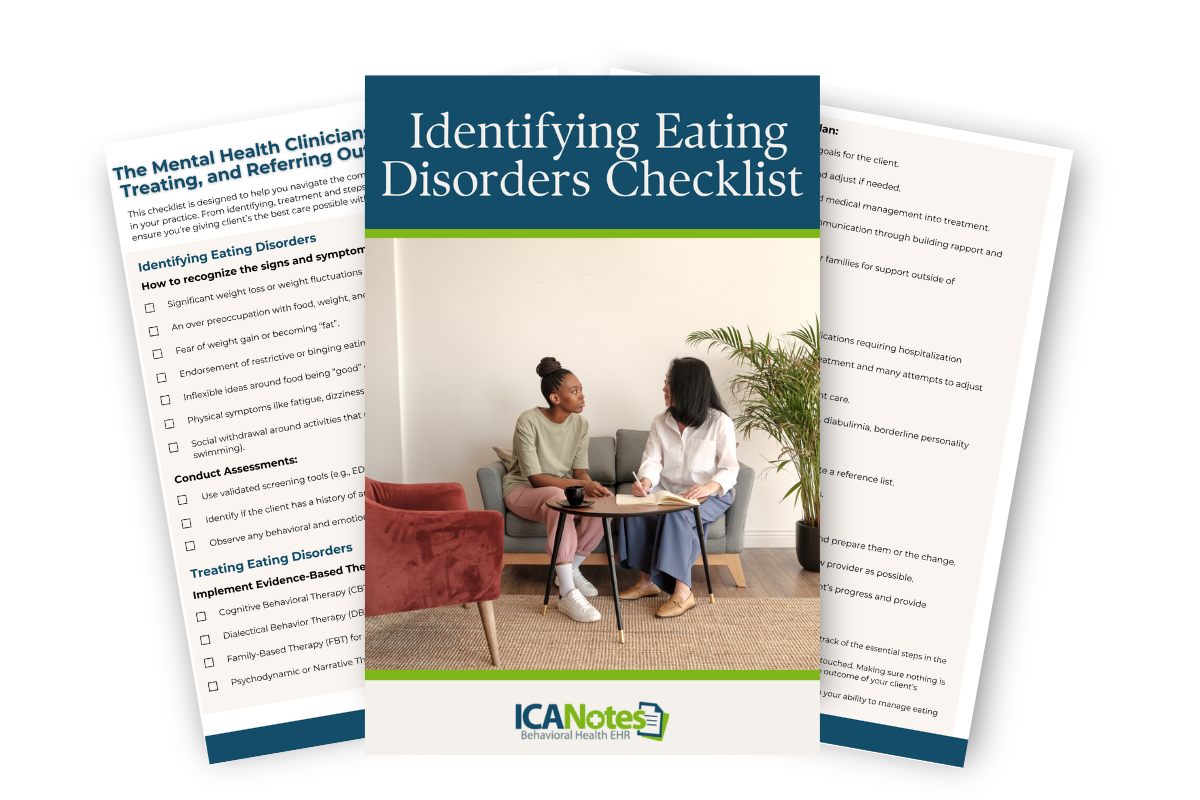

FREE DOWNLOAD: Download our Guide to Identifying Eating Disorders, designed to streamline the identification and treatment process for your clients. This comprehensive checklist provides clear, actionable steps to ensure you deliver the best care possible, boosting your confidence and improving client outcomes.

Orthorexia Nervosa: Not Yet an “Official” Diagnosis

Although it’s not yet recognized by the American Psychiatric Association as an official diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), orthorexia nervosa is recognized as a serious mental and physical health concern. Field experts hope that with more research and discourse, orthorexia nervosa will eventually be added to the DSM - helping educate communities, and increase access to treatment.[2] [3]

You might wonder - what’s the hold up? Currently, there is some debate regarding what symptoms make up orthorexia nervosa, and what differentiates it from mental health diagnoses like anorexia nervosa and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

More research is needed to validate, standardize and recognize orthorexia nervosa as a diagnosis in the DSM and International Classification of Diseases (ICD).[6] If/when added to the DSM, orthorexia nervosa will likely fall within the DSM-5 category of “Feeding and Eating Disorders.”[7]

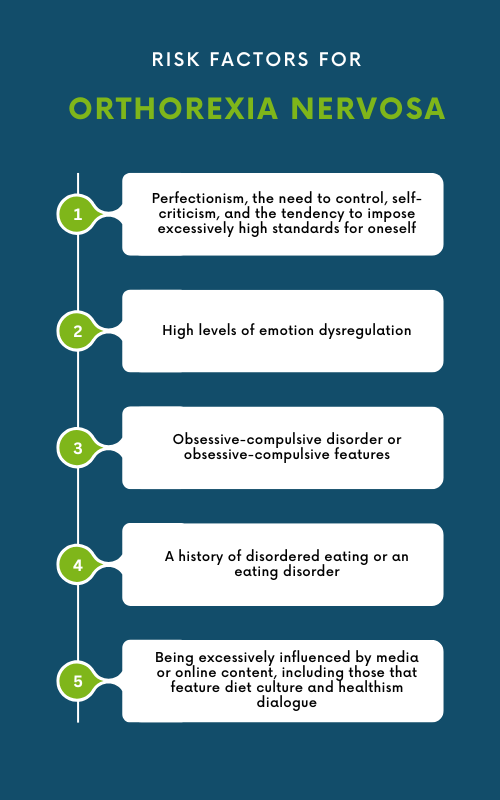

Who is at Risk for Developing Orthorexia Nervosa?

Orthorexia nervosa can impact anyone, but researchers believe there are specific risk factors that make some more likely to develop it than others. A combination of psychological and sociocultural influences play a part, and can include:

- Perfectionism, the need to control, self-criticism, and the tendency to impose excessively high standards for oneself[5]

- High levels of emotion dysregulation[5]

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder or obsessive-compulsive features[5]

- A history of disordered eating or an eating disorder[5]

- Being excessively influenced by media or online content, including those that feature diet culture and healthism dialogue[6]

Orthorexia nervosa may start as an innocent attempt to “be healthy.” Individuals may have concerns about developing specific diseases, especially if those things run in their family. Often, they are simply trying to promote health and be proactive.

The Role of Diet Culture and Healthism

Diet culture refers to societal messaging promoting myths around food, weight and health; including the idea that certain body types are better than others.[8] Heathism intersects and strengthens diet culture by messaging that health is the most important pursuit in life, that it is a personal responsibility, and that it is solely within an individual's control.

Together, diet culture and healthism heavily influence social settings and cultural norms that lay the perfect foundation for those predisposed to disordered eating or an eating disorder.

Signs and Symptoms of Orthorexia Nervosa

Although there is still work to do before orthorexia nervosa can be added to the DSM, significant progress has been made since the term was first coined in the 1990s. Criteria defined by researchers such as Bratman and Dunn, and later, Donini and colleagues has provided a crucial start to reaching consensus on an orthorexia diagnostic criteria.[7]

Building on top of the aforementioned work, a three-round Delphi study was conducted including 47 experts, from 14 different countries to provide a proposed agreed upon definition and criteria for orthorexia nervosa.[7] According to the Delphi study, orthorexia is characterized by:

- A strong preoccupation with one's eating behavior

- Self-imposed rigid and inflexible rules which are strictly controlled

- Adhesion to eating “healthy" food, often described as: pure, clean, organic, right, correct, natural or safe

- Avoidance of “unhealthy” food, often described as: processed, with added ingredients, prepared, treated, toxic, contaminated

- Spending an excessive amount of time for planning, obtaining, preparing and/or eating one’s food

- Emotional distress and/or anxiety if they are confronted with food they believe to be unhealthy and they fear they might be impaired by eating them

- Problems concerning attention and concentration (if an individual thinks about healthy eating all day)

- Feelings of guilt as a consequence of not being able to eat “healthy.”

- Such an adherence to self-imposed dietary rules that they have an undue influence on the individual’s self-evaluation.

Orthorexia nervosa is distinct from any eating disorder currently recognized in the DSM. Although symptomology overlaps with diagnoses like Anorexia nervosa and avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), the motivations of orthorexia are different and set it apart. Orthorexia nervosa centers on food quality, and a drive to be as healthy as possible.

Treatment for Orthorexia Nervosa

Due to limited research regarding orthorexia nervosa treatment, we don’t have evidence-based treatments lined up quite yet. However, there are some suggestions as to what best practices are for now. In line with the treatment of eating disorders, ideal treatment for orthorexia nervosa likely includes multidisciplinary work with a mental health therapist, registered dietitian, and medical doctor[5].

Treatment from the psychotherapist’s corner may include interventions such as psychoeducation about the condition, cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, family education, and family therapy.

Streamline Documentation for Orthorexia Treatment with ICANotes

Clinicians treating orthorexia nervosa need an efficient and accurate way to document their clients’ progress, diagnoses, and treatment plans. ICANotes simplifies this process with pre-configured, menu-driven templates specifically designed for eating disorder diagnosis and treatment. These templates support multidisciplinary approaches, enabling seamless collaboration between therapists, dietitians, and physicians. By reducing the time spent on documentation, ICANotes allows clinicians to focus more on delivering high-quality care, ensuring better outcomes for clients with orthorexia and other eating disorders.

How ICANotes Supports Multidisciplinary Treatment for Orthorexia

ICANotes’ intuitive, primarily click-based system empowers behavioral health professionals to create detailed, comprehensive notes in just minutes. With built-in tools for documenting symptoms, goals, and interventions, ICANotes gives you quick access to previous assessments and patient history. Whether you're tracking orthorexia nervosa symptoms, planning treatment goals, or coordinating care across a team, ICANotes ensures your documentation is both efficient and compliant, streamlining your workflow while supporting collaborative treatment efforts.

Learn more about ICANotes' tailored solutions for eating disorder care or schedule a live demo to see how it can transform your practice today!

About the Author

Katie Bendel - LCSW

Katie Bendel (she/her) is a therapist, writer, public speaker, and community connector. In her 10+ years of experience working in the mental health field, she has come to believe this:

As people, we thrive in – 1) authentic, empathetic, and vulnerable relationships with others 2) sense of safety – physically, mentally/emotionally, socially, etc. 3) connection to our values – what matters most to us. As a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW), Katie has dedicated her life to helping people access

that beautiful triad.

Katie has walked alongside thousands of individuals on various journeys, including those seeking eating disorder or substance abuse recovery, and those learning to cope with mood, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders. As part of this, she’s guided countless caregivers, family and friends who are eager to support their loved ones’ healing. Over the last decade, Katie has served in various roles such as individual therapist in the outpatient setting, clinical assessment for higher levels of care, residential program support (milieu coordination, group therapy, etc.), aftercare planning, resource development, community education (writing, speaking, etc.), and more.

Katie currently divides her time among various professional areas and settings. Her primary attention is with a national mental health treatment facility where she assists in resource development, community education, and facilitating peer-to-peer connection. In addition to this, Katie is a mental health therapist in group practice.

Sources

- Scarff J. R. (2017). Orthorexia Nervosa: An Obsession With Healthy Eating. Federal practitioner : for the health care professionals of the VA, DoD, and PHS, 34(6), 36–39.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

- Opitz, M. C., Newman, E., Alvarado Vázquez Mellado, A. S., Robertson, M. D. A., & Sharpe, H. (2020). The psychometric properties of Orthorexia Nervosa assessment scales: A systematic review and reliability generalization. Appetite, 155, 104797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104797

- Meule, A., & Voderholzer, U. (2021). Orthorexia Nervosa-It Is Time to Think About Abandoning the Concept of a Distinct Diagnosis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 640401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.640401

- Horovitz, O., & Argyrides, M. (2023). Orthorexia and Orthorexia Nervosa: A Comprehensive Examination of Prevalence, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Nutrients, 15(17), 3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15173851

- Ng, Q. X., Lee, D. Y. X., Yau, C. E., Han, M. X., Liew, J. J. L., Teoh, S. E., Ong, C., Yaow, C. Y. L., & Chee, K. T. (2024). On Orthorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Psychopathology, 57(4), 1–14. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1159/000536379

- Donini, L. M., Barrada, J. R., Barthels, F., Dunn, T. M., Babeau, C., Brytek-Matera, A., Cena, H., Cerolini, S., Cho, H. H., Coimbra, M., Cuzzolaro, M., Ferreira, C., Galfano, V., Grammatikopoulou, M. G., Hallit, S., Håman, L., Hay, P., Jimbo, M., Lasson, C., Lindgren, E. C., … Lombardo, C. (2022). A consensus document on definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa. Eating and weight disorders : EWD, 27(8), 3695–3711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01512-5

- The surprising history of Diet Culture. National Alliance for Eating Disorders. (2023, July 30). https://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/the-surprising-history-of-diet-culture/